Scales are a waste of time for advanced cellists!

It's been weighing on me, and I just had to get it out there.

Wait! Hear me out!

Unlike wind instrumentalists who use the same fingering for a scalar passage no matter what the context, string players must choose from a myriad of different finger patterns for the same passage based on many variables:

- Which notes come after the scalar passage?

- Which notes come before?

- What part of the scale am I playing?

- Will the passage be fast or slow?

- Should I use open strings?

- Do I want to incorporate string crossings?

- Do I want to maintain the timbre of a single string?

- What dynamic do I want to eventually achieve?

- Does the passage grow into the next notes or shrink away from them (or neither)?

...and I'm sure the list could be longer.

Scales do not present you with any of these contextual challenges. They can help you drill a certain fingering for scales that you MIGHT use for a passage once in a while, But that isn't enough for me. Why must my student work for hours and hours on learning all her scales for an audition while her solo pieces and etudes suffer? She can't spend 7 hours each day getting through all that mess.

I am asking the string world (please pardon the pun): Why are we forced to spend time on something that doesn't benefit us in a MAJOR way?

Defenders of scales say you need them because:

"That's what we've been practicing all along!"

"They get you out of the neck positions"

"They help you learn finger patterns"

BUT playing simple tunes in the key you want to target can provide the same results with the added benefit of contextualizing the patterns.

On the other hand, let's say you want to get really good at improvising in different keys.

Scales and arpeggios can help you internalize common finger patterns that you can then call upon when you launch into your blazingly amazing cello solo.

See, I'm not TOTALLY against scales.

"They ask for them at most auditions and juries"

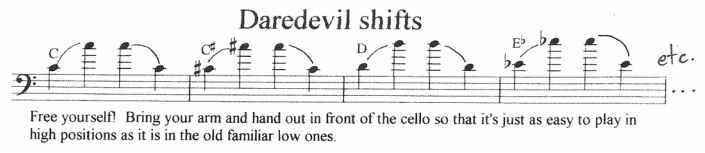

This will save you so much time when preparing for your All-State audition! The secret of this wonderful fingering is outlined in the excellent scale book my cello guru, Martha Gerschefski, wrote. In it she reveals the universal fingering for scales that makes D-flat major just as easy as D major. You can order The Road to Four Octave Scales and Arpeggios HERE.

"They give you time to work on technicalities without the distractions of music"

http://thestrad.com/latest/editorschoice/scales-and-exercises-are-essential-for-all-string-players-says-heinrich-schiff

I'm still not convinced.

Working out the technical stuff is called PRACTICE. If you are emoting constantly and being "distracted by the music" when you practice, you are doing it wrong! Much of your practice time must be devoted to training the motions of right and left arms/hands.

However the other time should be used to make decisions about the direction of the music. Considering this musical direction can actually inform your decisions about how you want to go about "programming" the motions. So, the drills of practice and musical expression are essentially always linked to each other, but not in a way that "distracts."

An exception to my disdain

Besides beefing up your improv chops, scales can help you train your ear. If you have difficulty hearing if you are in tune, playing scales with a tonic drone is a wonderful way to work on this problem without becoming distracted by what you are trying to say with the music.

Scales are nice and dry and boring, perfect fodder for focusing your mind on something else. Like your intonation.

"What should I be doing instead of playing scales?"

Also, there is no substitute for making deliberate fingering choices as you practice pieces and etudes. Choosing a fingering for a passage in a thoughtful way, taking into consideration all those contextual variables listed above, is what you have to do as a professional cellist. Why not get used to this job now?

If we did this each day, being very mindful about our fingering choices, I think we would become better cellists more rapidly than playing scales over and over without a real objective.

One last thought on the danger of scales

I know a child who loved the cello so much that extremely lengthy and in-depth practice sessions were like play time. Then this little cellist started studying with a teacher who spent the majority of the weekly lessons drilling scales. The little cellist soon stopped practicing. Stopped loving the cello.

Such a tragedy!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed